Charming Chervil.

Chervil has been left out of most modern cookbooks, and kitchen gardens. Maybe it’s time to bring it back.

Welcome to the Art of Growing Food newsletter. I write about artful growing tips for cooks who love to garden. You are receiving this newsletter because you are a free or paid subscriber. Thank you! - Ellen Ecker Ogden

Hello Everyone.

My grandmother sparked my desire to grow herbs. Maybe it wasn’t entirely her influence, but the lingering fragrance of thyme and rosemary in her kitchen turned me into a cook. She kept a large sun hat near the back door, and a wicker basket with a pair of large shears. When following her into the garden, the sweet waft of lavender and honey filled the air.

Waiting on a bench near the gate seemed endlessly long. She always had more to do: pulling weeds, pruning the tomatoes, filling up the watering can to give the plants a drink. I’ve learned that this often happens with gardeners; we are easily distracted and lose track of time.

I was lost in thoughts about what we would eat for lunch or dinner. The smell of soil clinging to the roots of the carrots as she pulled them from the ground nearby, brushing against the chervil (Anthriscus Cerfolium), nibbling it reminded me of licorice and black jellybeans at Easter.

A soft, ferny-leaved herb that tickled my tiny fingers as I rubbed the surface, like the short hair on a cat. It also tickled my tongue making it numb, unlike mint, parsley, or basil which was easy to sample. When I grew up and learned to cook for myself, chervil became an herb I learned to appreciate, perhaps because it was hard to find. I often gravitate towards growing what I can’t find in the store.

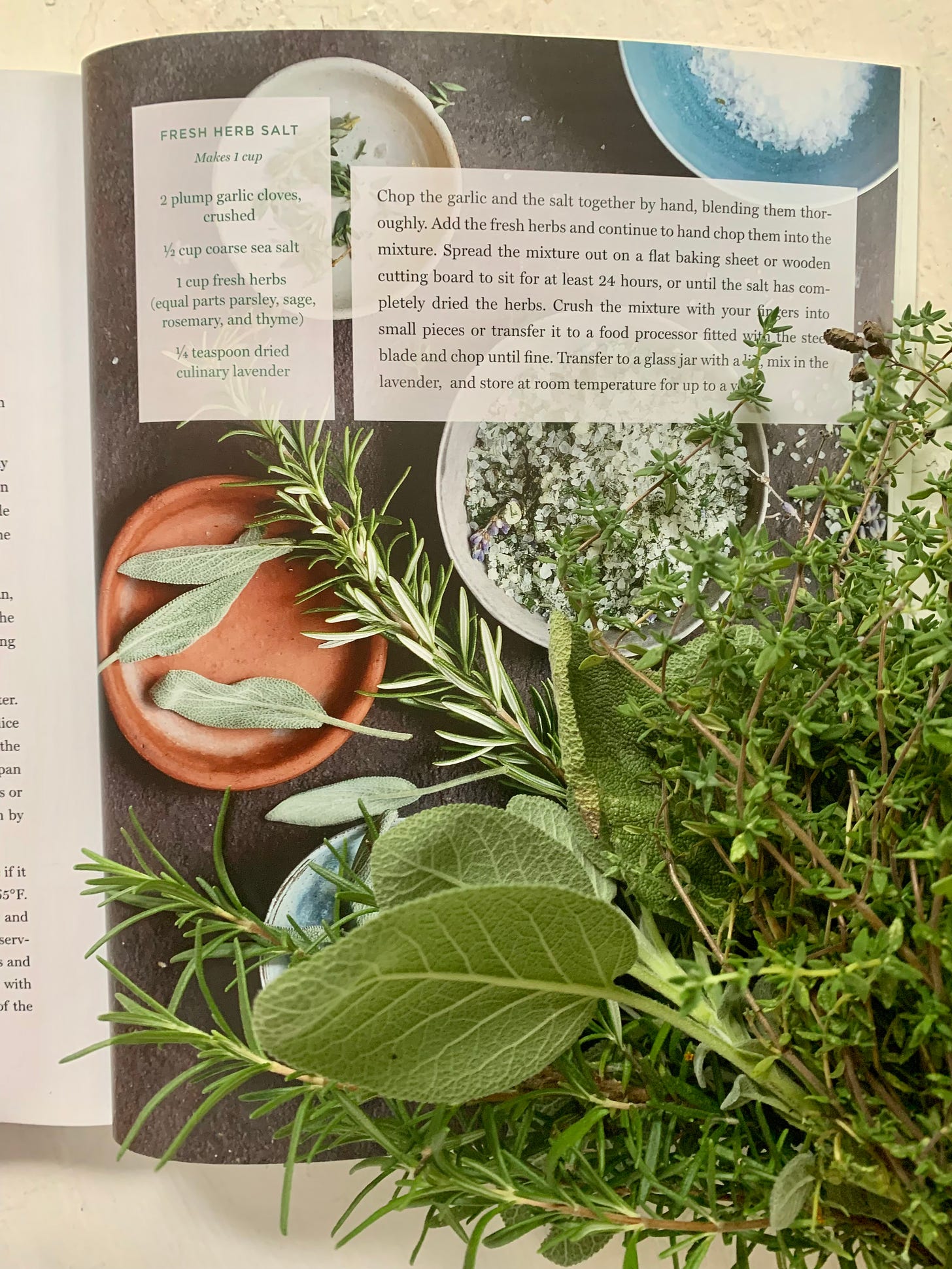

From the tea rose water my grandmother wore, the potpourri she made in flat baskets, and the aroma of herb bread baking in the oven, every herbal scent was expressed and magnified. Being with her encouraged me to slow down and inhale deeply. This is how I discovered that aromatics are more than a seasoning. Herbs infuse all the senses with heightened desire. As a result, I am never without culinary herbs, both fresh and dried.

When my grandmother moved from her big house to a smaller one, she asked what I would like to have from her home. I looked around and asked if I could have the herb poster on the kitchen wall above the table, pointing to a simple wood-framed print. It was probably the least valuable item, but I didn’t know to ask for a fancy antique or a painting. I just knew that this poster held the secret knowledge I needed to know; how to combine herbs with food.

At first, I tried to memorize the combinations shown in the chart: sage with beef; tarragon with fish; mint with vegetables, but there was a lot to remember. I hung the herb chart in my kitchen above the counter and referred to it often when cooking. I do not always follow the rules, but it has taught me how to make specific pairings and cook fluently with herbs as my second language.

When studying the herb chart more closely, I became curious about the few herbs not part of my cooking and gardening repertoire: Pennyroyal, burnet, lovage, costmary, and chervil. Somehow these herbs had fallen out of favor and were no longer considered integral to modern cuisine. I began to look for seeds, and her old cookbooks for clues as to how these herbs would be used in recipes.

Chervil is best grown from seed directly in the garden or a pot. Seeds are available at Wild Garden Seeds, Johnny’s, and Renees Garden Seeds which carry a fancy French variety.

Pure nostalgia enveloped me as I opened the pages of Tante Marie, splattered with sauce and drips from gravy. Handwritten notes on scraps of paper fell out of the pages, ephemeral moments containing obsolete information. But as I read the recipes, it was clear that the single herb Chervil' was the heart of sauces and dressing in French cuisine.

My grandmother shared a cooking style that matched the French housewife of many generations ago. She knew nothing of frozen or prepackaged food or the vitamin content, although she cared about good health. Like a good French housewife, she knew instinctively how to get the most flavor and nutrition out of every food. This often involved using Chervil, sometimes called French Parsley, the main constituent in the French herb mixture known as fines herbes.

A classic French recipe that features chervil is Potage aux Herbes (Herb soup) which begins by softening chopped lettuce in butter then a fistful of chervil, and other spring herbs before finishing with an egg yolk and heated cream. Or Crème d’Orseolle (Cream of Sorrel) soup made up largely of sorrel, sauteed with spring onions in butter and finished with cream and chervil.

Some of her French cookbooks also offered substitutions for chervil, by suggesting parsley and chive, in anticipation that it might go out of style. Yet once you taste the real deal, nothing can take its place. Even the smallest pinch makes a strong statement, just as arugula can do for a salad. Chervil has been left out of most modern cookbooks, yet maybe it’s time to bring it back.

In folk medicine, chervil is claimed to be a digestive, good for lowering high blood pressure, and when infused with vinegar will stop hiccups. I believe that Chervil has magical powers for longevity since my grandmother lived until she was 96. She smelled like rosewater and lavender until the end, and a small glass jar of her potpourri sits on my dressing table. When I cook, I sometimes consult the herb chart but by now I’ve mostly memorized it by heart.

From my garden to yours,

Ellen Ecker Ogden

Ellen Ecker Ogden is a Vermont-based food and garden writer, and author of five books on garden designs with recipes. She is currently writing a new book, Love & Arugula, and updating her kitchen garden designs. www.ellenogden.com

This article has all the best of garden writing — inspiring, evocative and accessible. Thank you.